This is the third time I’ve fled Sierra Leone because of a crisis. The first was in May of 2000 during the tail end of the war, when RUF rebels took UNAMSIL peacekeepers hostage. The second was July 2014, during Ebola time, just as people in Freetown were starting to take the virus seriously. And now, during corona time, after evacuating with the state department flight, I find myself hunkered down in the beautiful Shenandoah Valley in the U.S.A., missing my friends and colleagues at the University of Makeni where I had planned to be lecturing the rest of this academic year.

When I thought about writing this blog post, I naturally thought about reflecting on various policy recommendations, but to be honest, I am learning along with everyone else. I’ve learned a lot about the balance between “lockdowns and livelihoods,” particularly by reading other people’s blog posts, like this, this, and this.

I thought what I could contribute instead is a sense of what it felt like in Makeni, in Northern Sierra Leone, in the months and weeks before I left, and add some observations of how things have played out in the month since.

Echoes of Ebola

During March and April 2020, what kept leaping out at me was the multiple echoes of Ebola as Sierra Leoneans reflected on the difficulties of the present moment and imagined the difficulties to come.

One evening in late February, a friend and I were at our favorite drinking spot, and the television was showing a special on CNN on the lockdown in Wuhan, China. My friend was watching very attentively. Over the course of the hour, he shared stories I had never heard before, stories about his time supervising a burial team during the Ebola outbreak. I am often defensive of Sierra Leoneans when I remember how people in the West talked about superstitious Africans during Ebola, but I haven’t heard a single Sierra Leonean think that way. What I have heard is lots of sympathy, lots of understanding what it means to have people dying in large numbers and fighting an invisible enemy, living under lockdown and not knowing how to get food.

In the response to the corona virus, there are both pluses and minuses to having had the experience of Ebola. On the plus side, everyone knows about handwashing stations and testing and contact tracing. People know about death. People have already thought about the challenges of public health communication. For example, we talked about whether, in the local language, we should call the virus a “tumbu” (or maggot in English) or a “breeze” based on misunderstandings during Ebola outreach.

Some of the minuses are related to getting people to understand the ways COVID-19 is different from Ebola. While in Monrovia for a brief research trip, I saw a public sign board saying “Corona is real!” and “Don’t eat bush meat!”, both messages duplicated exactly from Ebola messaging, despite the fact that COVID-19 in West Africa has nothing to do with the consumption of bush meat.

On March 24th, a twelve-month ‘State of Emergency’ was declared by President Bio even before the first case appeared in the country. The Ebola experience meant people were generally supportive of the move. A few days later came the first three-day lockdown, not enough to really do anything to stop the corona virus, more like a trial run for lockdowns to come. Again, people were broadly supportive.

At the very end of March my friend and I went out drinking again. We ended up gathering with about six or seven people, one of whom was a member of parliament. We were joking about whether we should be gathering like that and asking the politician whether it was allowed to sing and dance under the state of emergency. It felt like normal life, with people saying “Let God protect us. We are still at zero cases. Maybe we’ll avoid it completely.” In those days we hoped we’d be able to keep the horror out by cancelling flights and closing borders.

All Politics is Local

Makeni is the city at the heart of the opposition All People’s Congress (APC) party. My palm wine drinking friends, mostly teachers, were suspicious that the lockdown was cover for President Bio of the Sierra Leone People’s Party (SLPP) to further their authoritarian actions, especially in the regions that were home to the opposition. One secondary school principal told me he thought the state of emergency could be cover for not paying government schools their state stipends.

All over Makeni, and in many other parts of the country as well, people listen on WhatsApp to daily audio reports from “Adebayor,” a Sierra Leonean living in Europe. Some call him a hot head, but many people in Makeni told me that his program is the only news they trust. Much of what he does on his program is reveal the alleged secret plans behind the SLPP government’s actions. His programs did a lot to sow mistrust among the APC faithful.

In addition to tracking the rumors on Adebayor’s daily message, I spent a lot of time listening to the local radio stations before I left. Two calls from listeners really stood out to me. The first was someone saying, “Now is not the time for human rights. We need to do what we can to curb the spread of the disease. Duya (please), let’s listen to government and do what they say!” Another was from a man saying, “Some of us lost our whole family to Ebola. We know this thing is real. Duya (please), take it seriously. The only thing we can do is pray, pray to God for his blessing.” To me, these messages are also about politics. The first showing the kind of talk that allows authoritarian politics to thrive and the second a kind of acknowledgement that government is not the highest authority after all.

Right before I left, another political event was on everyone’s lips. Paolo Conteh, the former defense minister under the APC and former head of the National Ebola Response Centre (NERC) was summoned to state house to speak with President Bio. At first, people thought this might be a good sign, a sign that the president was reaching across the aisle in order to bring those with the most relevant experience into the corona response. Instead, Conteh and his deputy were arrested for treason with the allegation that he brought a firearm into state house. Not too long after that, other APC stalwarts were arrested, including Sylvia Blyden and Daniel Y. Sesay, both for alleged “incitement and subversion.” Several friends in Sierra Leone are now telling me that the political turmoil is a lot more concerning than the corona virus (even though there are, as of this writing, 225 confirmed cases in the country.)

Social Distancing and Behavior Change

In my last few weeks in Makeni, I did not see much evidence that people were practicing “social distancing” and I wondered if they would be able to change their behavior. That said, I remember during Ebola time I doubted whether West Africans would ever be able to stop shaking hands, but eventually they did. Nevertheless, when I went to the bank in the center of town to pay for my evacuation flight, there were probably around twenty-five of us crowded around outside the bank waiting to get in. Then, once inside, the security guards tried to get us to stay six feet apart. Without the underlying understanding of how distancing works, it is being enforced haphazardly.

Another example: just me and a driver were in the car on our way to the airport. We stopped at a police checkpoint on the road just past Port Loko. The police had us both come down from the car and queue to wash our hands at a crowded hand washing station (with no soap!), lining up with all the passengers from a “poda poda” (van used for public transportation). I complained to the driver, “this is actually putting us at more risk!” but we had to comply.

These haphazard yet highly visible enforcement actions remind me of Ebola time as well. My colleague Nina Yamanis and I kept a blog while we were researching Ebola in Sierra Leone in 2015, and I wrote a post then about the “magical laser thermometers” that I thought did little to actually know who had a fever, but gave people a way to show they were doing something about Ebola.

In a lot of the world, the focus has been on ‘flattening the curve’ so that the health system wouldn’t be overwhelmed. But in Sierra Leone that logic doesn’t necessarily apply, since the health system starts out overwhelmed. Perhaps the best thing is just mass education about the virus and what to expect when one gets ill.

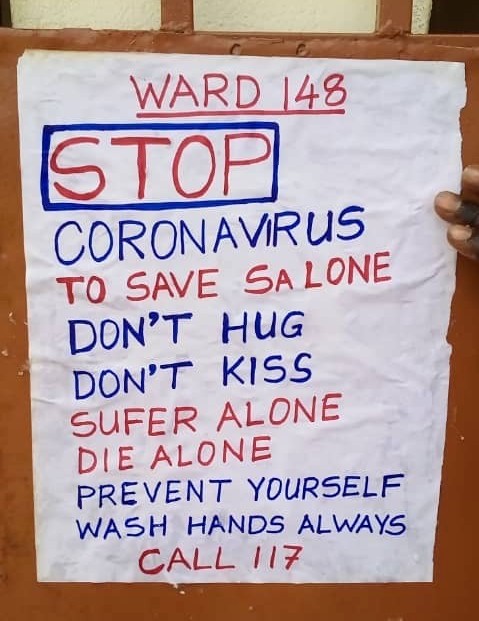

For now, the education on radio and elsewhere is mainly “Corona is real. Wash your hands. Stay at home.” And I know that people have a lot of misunderstandings and a lot of questions. My sense is that most people already believe it’s real, partly due to their experience with Ebola. Wash your hands is OK, but there’s not always soap or water available. And stay at home is very difficult. People are really not doing social distancing. More outreach is needed to communities where people don’t speak English or Krio. Some colleagues of mine at UniMak are working to translate WHO information into local languages and get people to go out and deliver it in person.

Recommendations, sort of.

If I had to recommend a course of action, my recommendations would be broad and based on respecting the knowledge and experience of Sierra Leoneans. In particular, I think there should be less militarized enforcement of curfews and other haphazard rules and more community-based education. And as we recommended during Ebola, the education message needs to shift in focus over time to meet shifting knowledge needs.

I am fully cognizant of the ‘passport privilege’ that has allowed me to leave my Sierra Leonean compatriots behind when crises have struck, but this time was a bit different. Sierra Leoneans asked me before I left “do you really’ want to leave here and go to the center of the outbreak?” Indeed, when I arrived at the airport in Washington DC, unlike in the Freetown airport, no one checked my temperature or asked where I was traveling from. The U.S. in fact has one of the worst official responses to the pandemic and some citizens are confused about the public health procedures and angrily demand they be allowed to flout them.

I hope to return to Makeni as soon as commercial flights are restored.